Once upon a time in New Jersey, our piney flatlands were home to not one, but two wild chickens – the heath hen and the ruffed grouse. We lost the heath hen long ago, beyond living memory, but the ruffed grouse has disappeared right before our eyes in the last 20 years.

In a 1986 article Pat Sutton wrote that ruffed grouse “abounded” in the Great Cedar Swamp of Cape May County and in the 1992 Cumberland County Delaware Estuary Study, ruffed grouse were considered to be “secretive, yet numerous” in that county’s big woods.

I have had only one encounter with a South Jersey ruffed grouse. It was the early 1990’s and I had just gotten my driver’s license and my first car. I immediately began to explore the local woodlands after school and on weekends.

This was before easy access to aerial photos or detailed maps. All I had was a map of Cape May County that I bought at WaWa.

It was true exploration, when I had no idea where a trail might lead.

While following a trail I’d never walked before one day in Belleplain State Forest, I found myself in a dense stand of Atlantic white cedar.

At this time of my life, the only way I knew to engage with nature was through hunting and fishing, so I was out with my shotgun in search of small game.

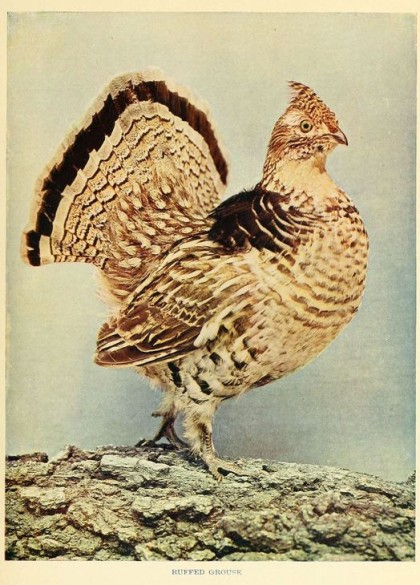

In front of me along that cedar-hemmed and darkened trail, up flushed a ruffed grouse. The spreading fan of its tail was unmistakable as it took flight through the tree limbs to escape.

I admit that I took a shot at it, and also admit that I missed it entirely!

I left for college shortly after that grouse encounter. I had no idea that would be the last grouse I might ever see in south Jersey.

Sometime shortly after I harassed that Belleplain grouse, South Jersey grouse disappeared entirely.

Christmas Bird Count data is very helpful for pinpointing when the disappearance happened.

CBC counts in South Jersey’s woodsiest areas began in 1959 in Cumberland County and late in two other deep-woods regions: the Pine Barrens (started in 1979) and Belleplain (started in 1988) . Each of these count areas appear to have had grouse present when they were started, but grouse have not been seen in any of these Christmas Bird Count areas since 1999.

If we look at state-wide ruffed grouse detections during the Christmas Bird Count over time, we can see that the range of the ruffed grouse has contracted considerably. At the peak, roughly half of all the count areas in the state detected grouse. Now, grouse are seen in just one or two circles in the northern mountainous regions of New Jersey.

Although the graph above shows a bell curve, I think the increase between 1900 and 1980 probably represents an increase in count circles added to the CBC network. The decrease after 1980, on the other hand, likely reflects a real range contraction of ruffed grouse.

This range contraction is confirmed in The Birds of New Jersey, where the map for ruffed grouse shows the current and former range of the bird:

All of this leaves us wondering: what happened?

One strong possibility is that grouse habitat has changed. Research has shown that ruffed grouse thrive in young forest and forest that is from 0-7 years old is especially important for brood rearing.

In the northeastern United States, a lack of such young forest habitats is a looming conservation crisis, not only for grouse but a wealth of other species that depend on these early stages of growth.

“They thrive best where forests are kept young and vigorous by occasional clear-cut logging, or fire, and gradually diminish in numbers as forests mature and their critical food and cover resources deteriorate in the shade of a climax forest.” – Grouse Facts, The Ruffed Grouse Society

We’ve lost the natural processes that create younger forest like fire and beavers. But, because of changing economics conditions, we’ve also lost the “working landscapes” where trees were cut for lumber and firewood — in ways that well-enough mimicked natural disturbance to keep ruffed grouse happy (but perhaps not well enough for the extinct heath hen!)

Based on my knowledge of the place where I saw my grouse, I am slightly dubious that habitat change is the whole story.

Here’s the evidence:

Gypsy moths hit Belleplain State Forest hard in the 1980s. Tens and perhaps hundreds of acres of mature oaks were killed. And salvage clearcuts were carried out at several sites throughout the forest. I vaguely remember leveled forest not far from where I saw my grouse.

And fortunately, someone put up some signs with dates throughout Belleplain State Forest:

Based on these dates, ruffed grouse disappeared for good in Belleplain just ten years after large swaths of forest were leveled to the ground that would have theoretically improved habitat quality for the birds.

To my knowledge no cuts have happened since, but the timing of ruffed grouse disappearance doesn’t seem to fit with the idea that there was a lack of young forest at the time.

Other possibilities that have been suggested for the decline of grouse in New Jersey and elsewhere are West Nile Virus (first detected in the U.S. in 1999) and deer overabundance.

Grouse are browsers just like deer, feeding on tree and shrub buds in the winter months. Deer might be getting to all the good eating before the grouse do.

And even when trees are cut to create early successional habitat, at high densities deer can hinder tree and shrub regeneration. They can also alter what trees and shrubs regenerate through selective browsing, so that only the unpalatable plants thrive.

Unfortunately I don’t have answers for why grouse disappeared in South Jersey or for why they are even becoming less common in their mountain strongholds in north Jersey. I suspect that forest age, although a big part of the story, isn’t the whole story.

We are losing a once-common species right before our eyes. And this isn’t some obscure bird only a handful of people care about, it is an iconic game animal (with its own society, no less). Yet we seem to be unable to do anything to stem the loss of these birds in New Jersey.