Read more about the tide and Bear Swamp in the news: “Old Trees on the Brink” at the Philadelphia Inquirer

Clay Sutton compiled these quotes from the work of Dallas Lore Sharp. Sharp was a Cumberland County NJ native and prolific nature writer during the early years of the 20th century. More than 100 years later, every word still applies to Bear Swamp.

Thanks to the efforts of the state of NJ and Natural Lands, all of the remaining old growth is protected, 200 acres of it embedded in a larger natural landscape that comprises more than 30,000 contiguous acres of forest, marsh and former farms.

The swamp is not unscathed by development. The two old growth stands are separated by big and very deep sand mine pits. Sand has long been an economically important natural resource in South Jersey and its availability here made the region famous for glass-making. The glass industry (and jobs) are gone but sand mining remains. It is now, in many cases, in the hands of large multinational corporations.

It is difficult to estimate the amount of old growth forest that remains in the world, despite its ecological importance and public appeal. You can find a map for anything, but I challenge you to find one for old growth. This seems to be partly because it is difficult for professionals to agree on what defines “old growth”.

But Bear Swamp must be one of the largest tracts of old woods in the Northeast (check out this link for one excellent attempt to catalog old growth forests in the eastern U.S.).

A visit to Bear Swamp is an event. It is lives up to its mystique by existing in a remote location with no trails. The heart of the big woods is just one mile from a railroad right-of-way, but swampy ground and dense, thorny undergrowth make that mile feel like an expedition.

Once you arrive, you will not be disappointed. The trees are absolutely huge in girth and height, perched on mounds of ancient roots that keep the tree boles elevated above the standing water of the swamp. The broad trunks ascend to canopy branches in various states of disrepair. Many of the old trees have lost major limbs in storms, making them look like partial amputees.

Scientists who sought to age the trees quickly discovered that nearly all of the biggest trees are hollow. The hollowness doesn’t appear to affect their health. All of a trees’ living tissue sits just beneath the bark and the hollowness may actually confer structural integrity while reducing the amount of weight that must be kept upright in the swampy ground.

An added benefit is that such a hollow tree is worthless for timber. This ultimately may be why they were spared the saw.

Black Tupelo and Sweet gum are the stars of the big-tree show, but there are also some very big red maple, tulip trees and even a few oaks. Sweet bay magnolia, which typically has slender trunks that reach the subcanopy, can be nearly 100′ tall here.

All this impressive woodland hosts an equally impressive roster of wildlife species. Naturalists who conducted bird surveys there concluded that 119 species nest in the swamp. This includes many species that would be considered birds of southern forests such as Louisina waterthrush and prothonotary, hooded, yellow-throated and Kentucky warblers. It is also one of the few place in South Jersey where pileated woodpeckers can be found.

Despite its protected status, a new threat to the forest is emerging.

Bear Swamp occupies lowlands that are just a short distance from tidal marsh. The progression of sea level rise is allowing these marshes to gradually overtake uplands and freshwater swamps, as it has since the Laurentide glacier melted 10,000 years ago. The weight of the glacier caused the land of south Jersey to lift upward. Since that weight is gone, the land has since been settling downward at a steady rate of 3mm a year. This adds up to a foot a century.

The uncertainty now lies in how much global climate change will accelerate the rate of sea level rise.

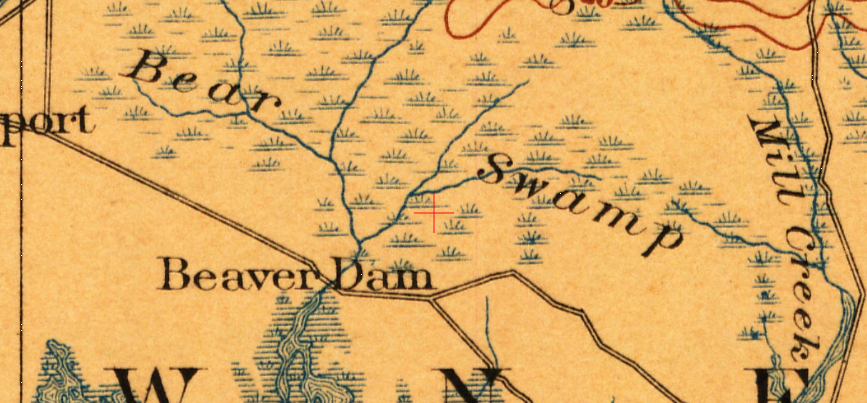

Bear Swamp sits in a micro-valley, with a natural sand ridge running along its western flank and an artificial spoil pile from the sand mine bounding its eastern edge. Between these two bits of high ground, the southern edge of the forest meets the tidal marsh.

Here, year after year, the marsh is gradually overtaking the forest as one by one, trees gradually succumb to elevated salinity. On a recent visit to the swamp it was apparent that some of the big trees will soon be feeling the sting of salt and it is possible that others have died already.

I’ve made salinity measurements along the forest and salt marsh edge and have noticed different species of trees and shrub have varying tolerances, but above around 6 parts per thousand salinity, forest plants are dying or at least showing signs of stress.

Seven years ago I made a surprising observation in the sand pit adjacent to the old growth. The pit, which typically would be full of fresh groundwater, was brackish. Salinity readings were 3.5 parts per thousand.

At the time I was ascending tidal creeks all along the bayshore to document salinity gradients for a paper on forest dieback and inland marsh migration.

The source of the salinity was Oranoaken Creek. The creek once rose in the headwaters of Bear Swamp, but it became truncated when the sand pit replaced a large part of the forest. For decades the creek and pit were separated by a thin band of swampy woods. But over time, with the rising sea, the head of tide in the creek moved upward into the woods and eventually crossed the threshold into the pit.

The tides now surge into the pit twice daily to mix with the massive volume of groundwater there. The result is what is known as a “novel ecosystem” — a human-created ecosystem that lacks a natural analog.

There is no natural analog to a brackish sand pit: a large and deep lake that is mildly brackish which mingles surface water with groundwater at the upper reaches of tidal creeks.

A distinguishing feature of our novel ecosystem is stability with regard to salinity and temperature. A natural headwater environment would vary as seasons and precipitation patterns change. I often wonder what lurks in those depths. What creatures are making use of this new habitat?

I have heard that there are blue crabs in there. And there is likely an odd mix of freshwater and estuarine fish occupying it.

The effect of the brackish water in the sand pit on the old-growth next store is also unclear. I was prompted to reconsider this after talking to a reporter, Frank Kummer, from the Philadelphia Inquirer who was investigating the impacts of sea level rise on the Delaware Bay coastline.

After talking to him and sharing my observations of the brackish pit, I felt compelled to return to the pit to see how the salinity had changed since 2011.

The readings have indeed changed. As of fall 2018, the salinity is now around 8.2 parts per thousand. This is considerably higher than what I measured before and, once again, the readings are consistent anywhere in the pit at the surface and down to 20′ depths.

The increasing salinity enhances the urgency of determining the influence this salty pit is having on the adjacent woods.

For now, working with Natural Lands staff, we will continue to monitor changes in the pit and to the old growth forest and this monitoring will help identify any actions that can help slow down the effect of sea level rise and the legacy of sand mining on Bear Swamp.

If the Bear Swamp forest was just another swath of second or third-growth forest, we might welcome the transition from forest to marsh. Allowing this process to occur is essential for offsetting losses of marsh at the seaward edge as sea level rise progresses.

But in this case, managers may choose actions that protect the old growth from change because it is, in today’s landscape, unique and irreplaceable.