I began reading Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science by author Carol K. Yoon expecting a history of modern scientific nomenclature starting with Linnaeus, peppered with some trivia on the quaint and quirky ways that other cultures and eras approached nomenclature. The author admits that she herself had such expectations as she began plotting the book. She certainly meets these expectations, but she also introduces a profound concept – that there is a difference between reality and the human perception of reality and that this difference can explain some vexing things about human nature.

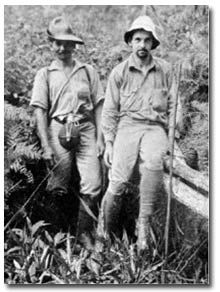

Yoon realized that until very recently, the ways people in other times and cultures gave names to things was little different from how western science had been doing it well into the 20th century. For example, venerable taxonomist Ernst Mayer classified New Guinean bird fauna in nearly the same way as native hunter-gatherers with no formal training in such things. As Yoon discovered, both the New Guineans and the western taxonomists used what seems to be a hard-wired approach to organizing plants and animals that is closely linked to the way human senses have evolved to perceive the world.

Ernst Mayer (right) in New Guinea

To refer to this uniquely human perception of reality, the author dusts off the German word umwelt. Umwelt means something along the lines of, “the world as it is perceived (not the world as it truly is).”

Our perception of the world is tuned to specific temporal and spatial scales and this shapes our understanding of the world—our umwelt. But many real phenomena—e.g., particle physics, plate tectonics—cannot be perceived by our umwelt. Another key example is evolution. Understanding evolution requires a certain faith. It is a continual process, and yet it does not appear to be happening at all. We do not perceive evolution. We perceive what appears to be a static world composed of an array of discrete species.

Related to this, science has long struggled to settle on a definition for “species”. Definitions come and go with no satisfying resolution. To Yoon’s way of thinking, this is evidence of our umwelt‘s struggle with reality. There really may be no such thing as a species, despite what our senses tell us. “Species” may merely be a series of still frames from an endlessly moving picture.

Given that scientists themselves struggle against their innate perception of the world, it’s not surprising that evolution is so difficult for many people to accept, despite overwhelming evidence and a legion of books written to impress this truth upon the laymen. Given the faith required, it’s also not surprising that evolution is often couched in terms of belief: “Do you believe in evolution?”

The umwelt’s intuitive perception of the world that is sometimes in conflict with the way things really are can help us understand the resistance encountered when we attempt to convince people that issues like climate change are important. A giraffe has been a giraffe for as long as anyone (or anyone’s ancestor) can remember. The same is true for the climate. Natural changes in climate come about gradually. A static, predictable world is what we expect unless we are convinced otherwise.

The ideas introduced in Naming Nature may offer some help in our attempts to make sense of how humans relate to the natural world, the science that attempts to explain it, and the conservation that attempts to save it.

(This review originally appeared in the December 2010 edition of the Nature Conservancy’s Science Chronicles.)