Listen to this Delaware Bayshore black rail (along with, I think, gray tree frogs and toads) recorded in 1961:

Will there be a black rail singing at this location near Fortescue this spring ?

Thanks to NJ Audubon and the Cape May Bird Observatory, we might find out.

Much of what we know about New Jersey black rails in modern times we owe to Paul Kerlinger and Clay Sutton. They conducted surveys in the late 1980s throughout New Jersey in places where black rail had been documented historically. The NJ Audubon effort will be the first organized survey of black rails in New Jersey since then.

During the 1980s survey, most of the black rails were found on the Delaware Bayshore, primarily in Cumberland County. The Atlantic Coast barrier islands once were a hotspot for the rails, but by the late 20th century the islands were transformed beyond all recognition (from a rail’s perspective) and black rails were mostly gone.

The key habitat feature for black rails, at least in New Jersey, is the presence of high marsh vegetation.

According to Kerlinger and Sutton,

“Most of the Black Rail sites we located had at least some patches of S. patens (salt hay) mixed with other grasses and rushes as well as Spartina altemiflora and some Iva (marsh elder). Sites where the most Black Rails were found were near the upland edge of the marsh. These sites are rather dry and are inundated rarely by high tide.”

Maybe what they are describing looks something like this:

We can’t talk about salt hay on the bayshore without talking about salt hay farms. In the early 20th century, much of the bay’s marshes were a tamed landscape of ditches, sluices and dikes that carefully throttled tidal waters to grow salt hay in an easily managed and harvested setting.

Salt hay farms may have also been black rail farms. They created a stable nesting environment of lush high marsh vegetation that was completely protected from flooding by the hay farm dikes.

The only downside of nesting on a hay farm is that you or your nest might get mowed. But across all of this vast area of farms there were likely inaccessible nooks and crannies where black rails remained unmolested by hay cutting.

All was well for high marsh specialist bird species for a long time on the bayshore. But over the course of the 20th century the lay of the land changed dramatically. Salt hay farming became less profitable and, with dikes and sluices needing constant repair and maintenance, one by one the farms were let go.

Now, for the most part, these lands are now owned by conservation non-profits and state and federal agencies. When the farms went, so did the high marsh vegetation. Most of these areas are now devoid of high marsh as low marsh recolonized the former hay farms.

Kerlinger and Sutton tell us that:

“Large expanses of appropriate habitat (salt hay marsh) are needed to maintain a healthy population in southern New Jersey.”

We’ve now lost many of these large expanses .

The best two examples of the loss high marsh habitat with the loss of hay farms are the two most recent.

Into the 2000s there were two major salt hay farms left: one near Turkey Point (375 acres) and one near Jakes Landing (300 acres). Is it a coincidence that these two places happen to be the most consistent spots to hear black rail in recent times?

Turkey Point was considered to be the epicenter of the black rail population during the 1980s

“The long-term presence of Black Rails at Turkey Point demonstrates that central Cumberland County marshes are the most important breeding habitat for the species along the Bayshore.”

And Turkey Point has paid black rail dividends all the way up to 2010, according to Ebird.

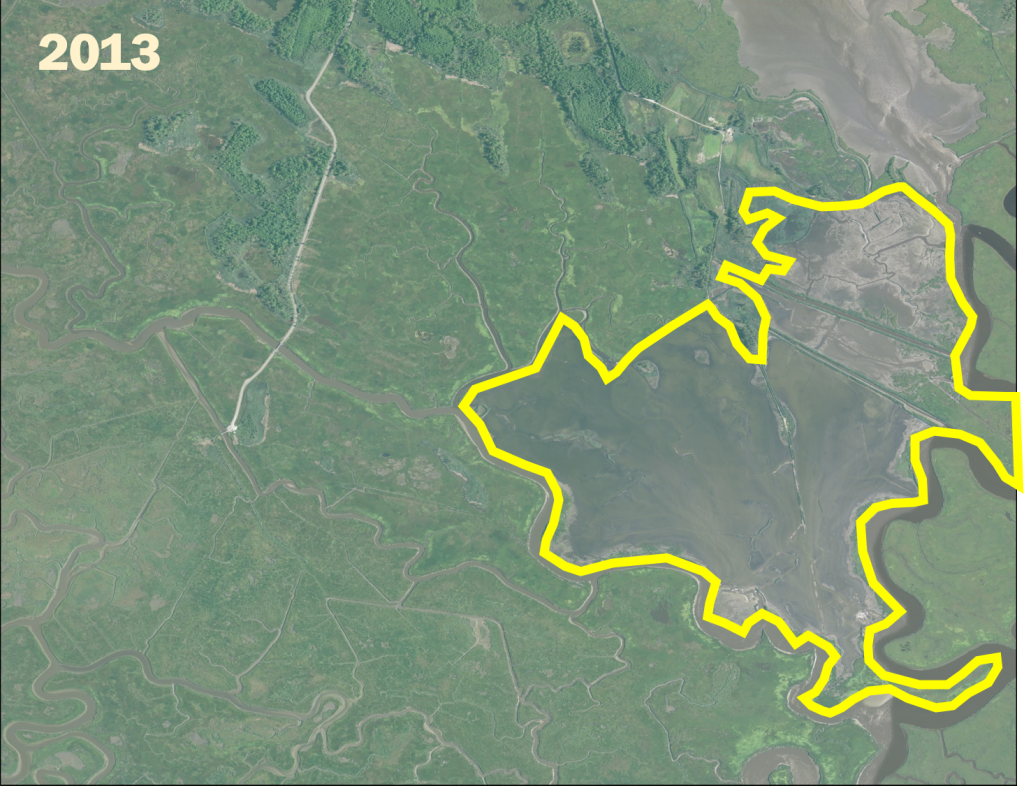

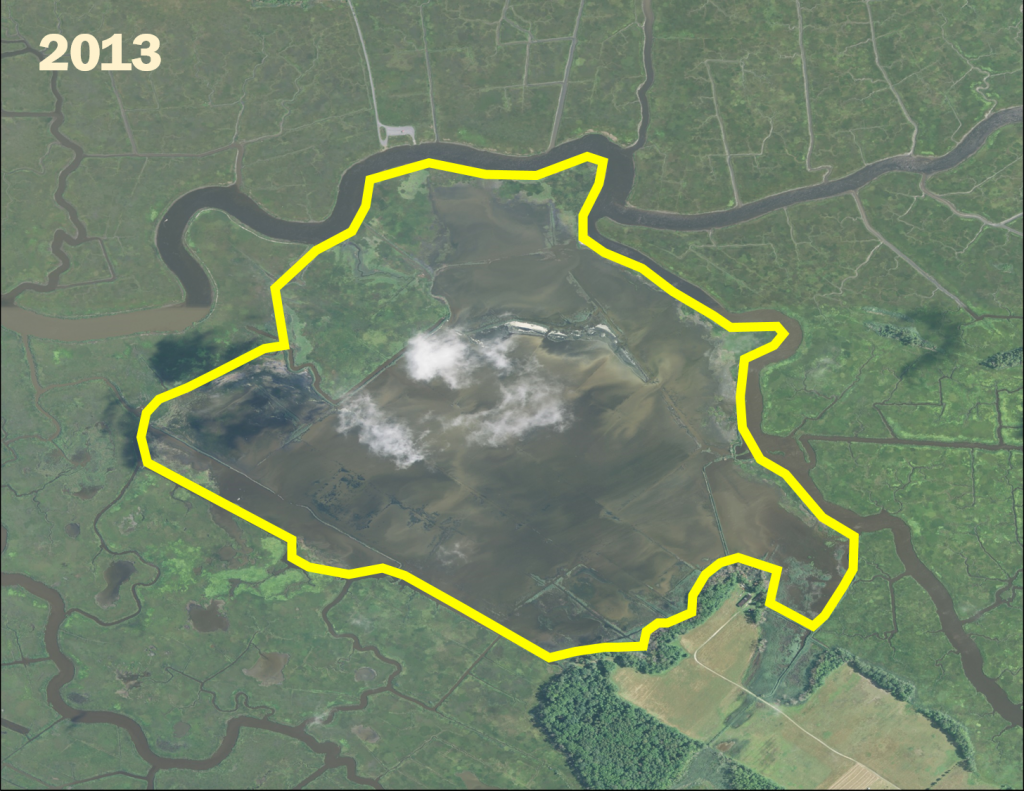

But a catastrophic dike breach in the winter of 2008-2009 resulted in the instantaneous loss of 375 acres of high marsh vegetation that is now mostly flooded mudflat.

The story is similar for the hay farm near Jakes Landing. Hurricane Sandy knocked holes in the dike and again, the transformation was instantaneous. The 300 acres of salt hay is now a mudflat. (read my “Opposite of resilient” post for an explanation of the process)

The last report of a black rail on Ebird at Jakes Landing was 2011.

It could be that birders are keeping quiet about their black rail observations in recent years or it might have something to do with the loss of the last two massive areas of high marsh habitat on the Delaware Bay.

There is nothing else like these places left.

The question now is, how much high marsh does a black rail need to get by?

Looking at the historical geography of the bayshore salt marshes, we find that most of the marsh from Cape May up the Maurice River and west to Dividing Creek was wall-to-wall diked farm. But fortunately, the stretch between Dividing Creek over to the Cohansey River seemed to experience a lighter touch with less wholesale transformation of the landscape.

This region’s marshes have a somewhat more natural character and might be our best hope for finding extant populations of black rails, as long the rails can survive in a habitat mosaic that consists of smaller patches of high marsh.

The map below shows some of the late 1980s rails detections with a high marsh patch density metric that I created based on a high marsh map (excluding hay farms) I made for 2006.

You can see that the darkest green areas are to the west in the region that had less salt hay farming in earlier decades.

Now what of George B. Reynard’s 1961 black rail? How has that spot fared over the 55 years since that recording was made?

I have high hopes for George’s spot.

Compared to other places, it has changed little and still has a respectable amount of high marsh adjacent to some upland edge.

I happen to have a photo taken almost exactly at Reynard’s spot. Looks pretty enticing doesn’t it?

I am not sure the frogs and toads are still holding on out there (it is looking salty), but, for rails, I think it is worth a midnight ride out Fortescue Road to take a listen.